I played it in February, but Firewatch was my own personal summer camp. It offers a delightful, if sometimes melancholy and mysterious, departure from urban life with a vast expanse of nature to explore at your leisure.

A game that was highly anticipated, generally well-received at launch, and subsequently second-guessed for not being as life-changing as people thought it should have been, Firewatch is still an experience that sticks out in my memory as a very personal journey inward experienced through the eyes of a man searching for an escape (and maybe newfound purpose) after a period of loss and grief.

I'm not typically a fan of pickup trucks, but you leave this one behind pretty quickly.

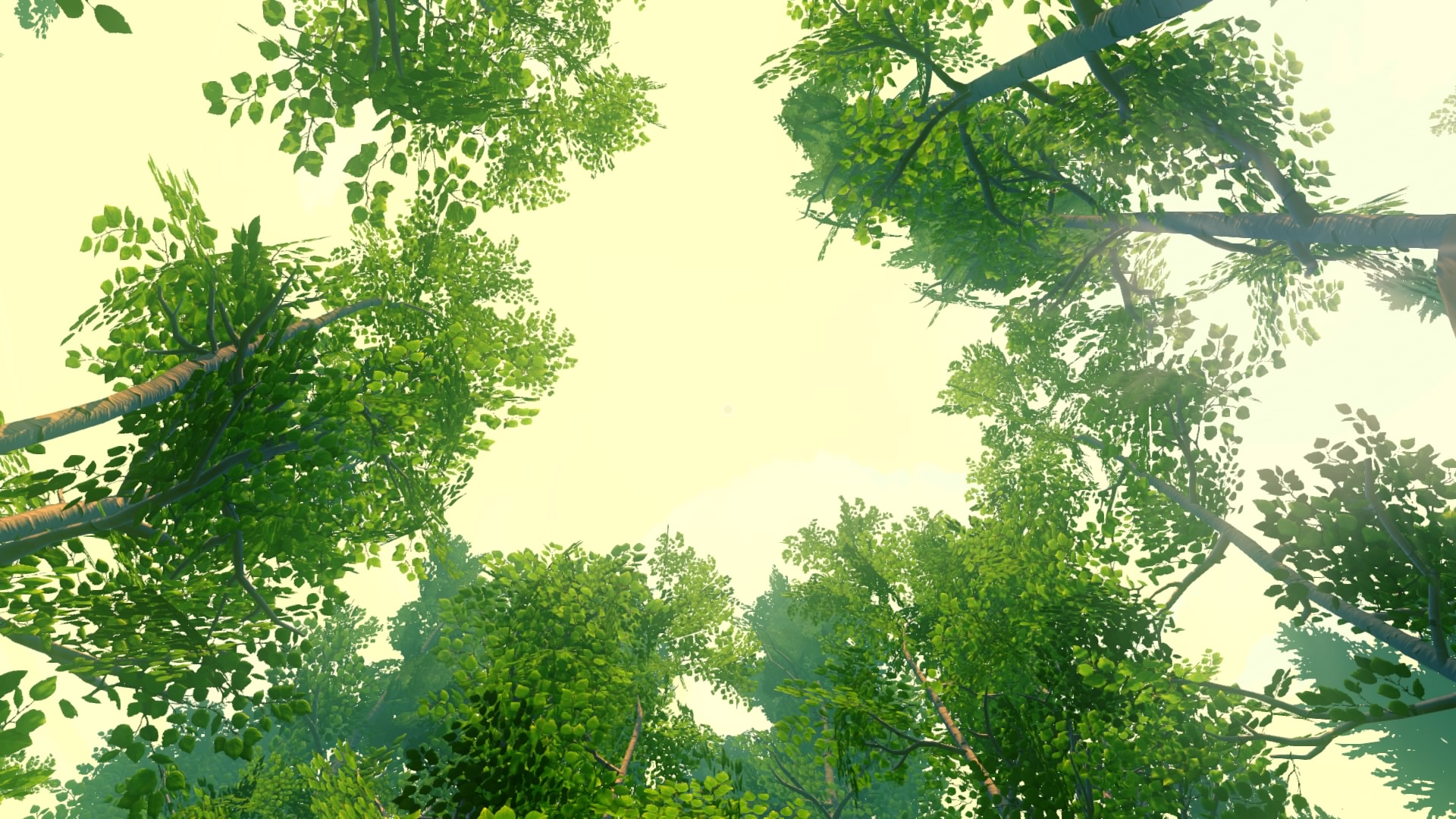

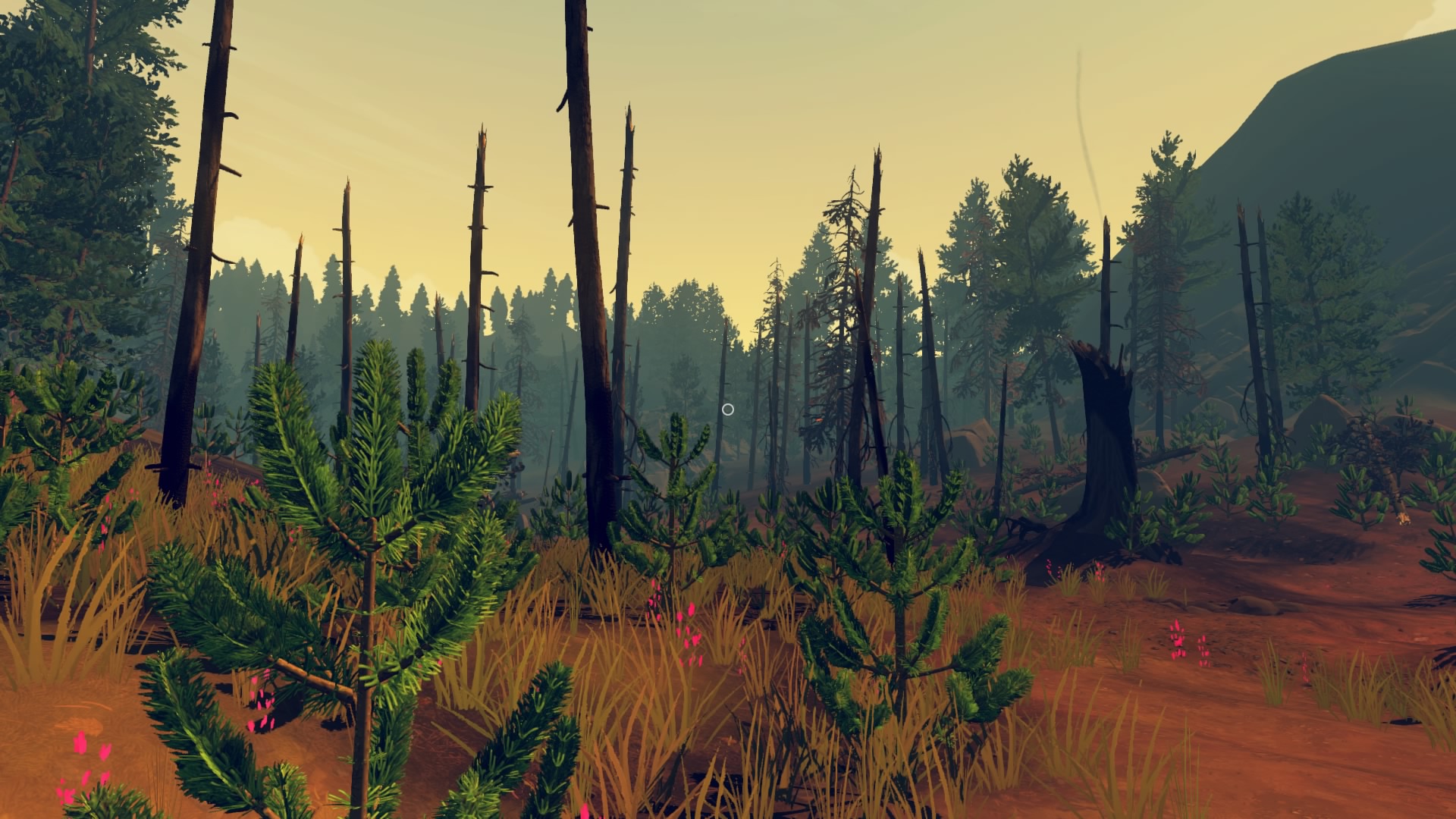

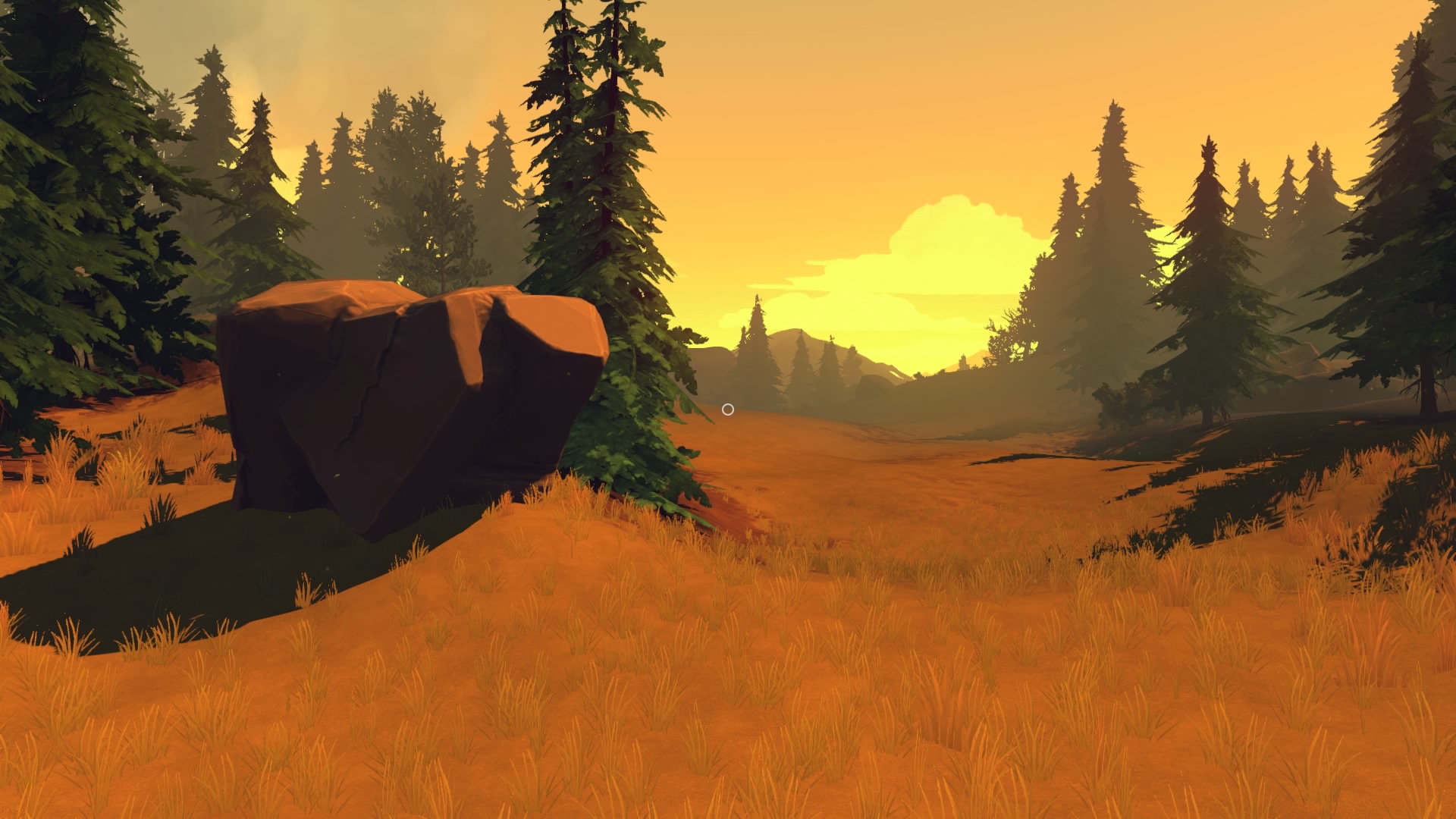

Before we get into all the deep stuff, though, let's just start with the visuals. It's easy to see the game is gorgeous, using a slightly cartoonish aesthetic to great effect in creating its national park/forest preserve setting.

The sunlight plays off the rocks and trees realistically, and the moonlight perfectly creates mysterious shadows in the night. Through clever use of rock outcroppings, hiking trails, streams, and fallen logs, the developers craft a visually interesting world that also functions as a logical play space. Throughout my four or so hours in the game, I spent many minutes just gazing at the scenery, listening to the forest, and enjoying the virtual fresh air; it captured all the delight of a hike with none of the annoying bugs.

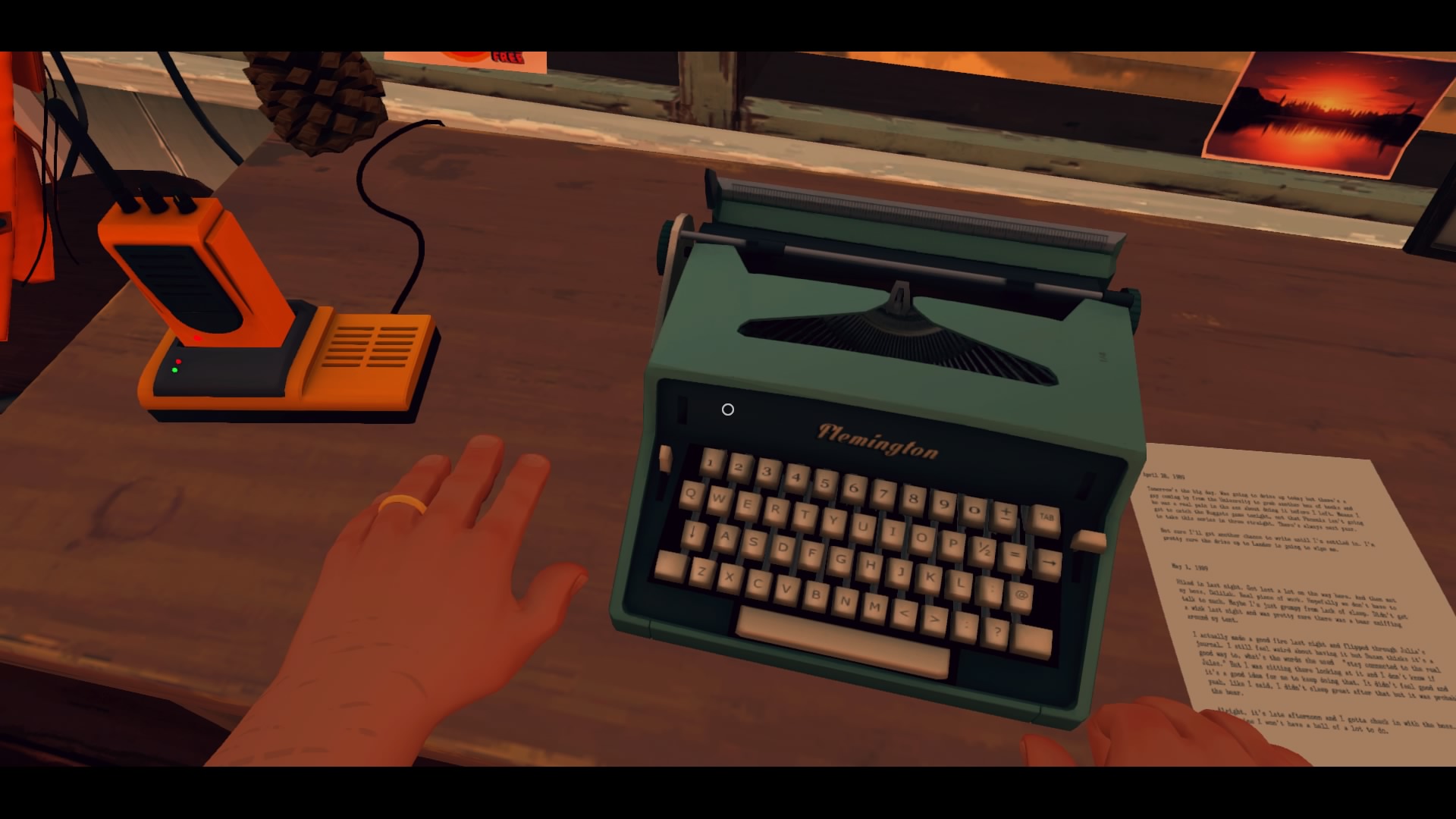

There's, of course, a story to enjoy, too; in fact, that's about all there is to the game (i.e. there's no combat or puzzle solving). You play as "Hank," a man escaping his once-happy marriage to a woman suffering from early-onset Alzheimer's disease by taking a job as a fire tower lookout in a national park during the summer of 1989. Mainly, you walk around, talk to another lookout, Delilah, and slowly unravel the mysterious history of some of the park's former visitors.

The game's opening gives you a series of scenarios to help flesh out Hank's past.

Before you do any of that, though, the game starts off in a most unusual fashion: with a series of text-based prompts, asking the player to react by multiple choice.

For a game so intrinsically tied with visual exploration, it's a surprising choice. It was likely chosen as a device to help keep additional development costs down for Campo Santo, the game's very small independent developer; however, it has the effect of focusing the player on raw narrative before you experience the visual beauty to come. The drab, dark colors of the text-only screens mirror Hank's dark, clouded past where there are only fuzzy memories of events, not faces or places.

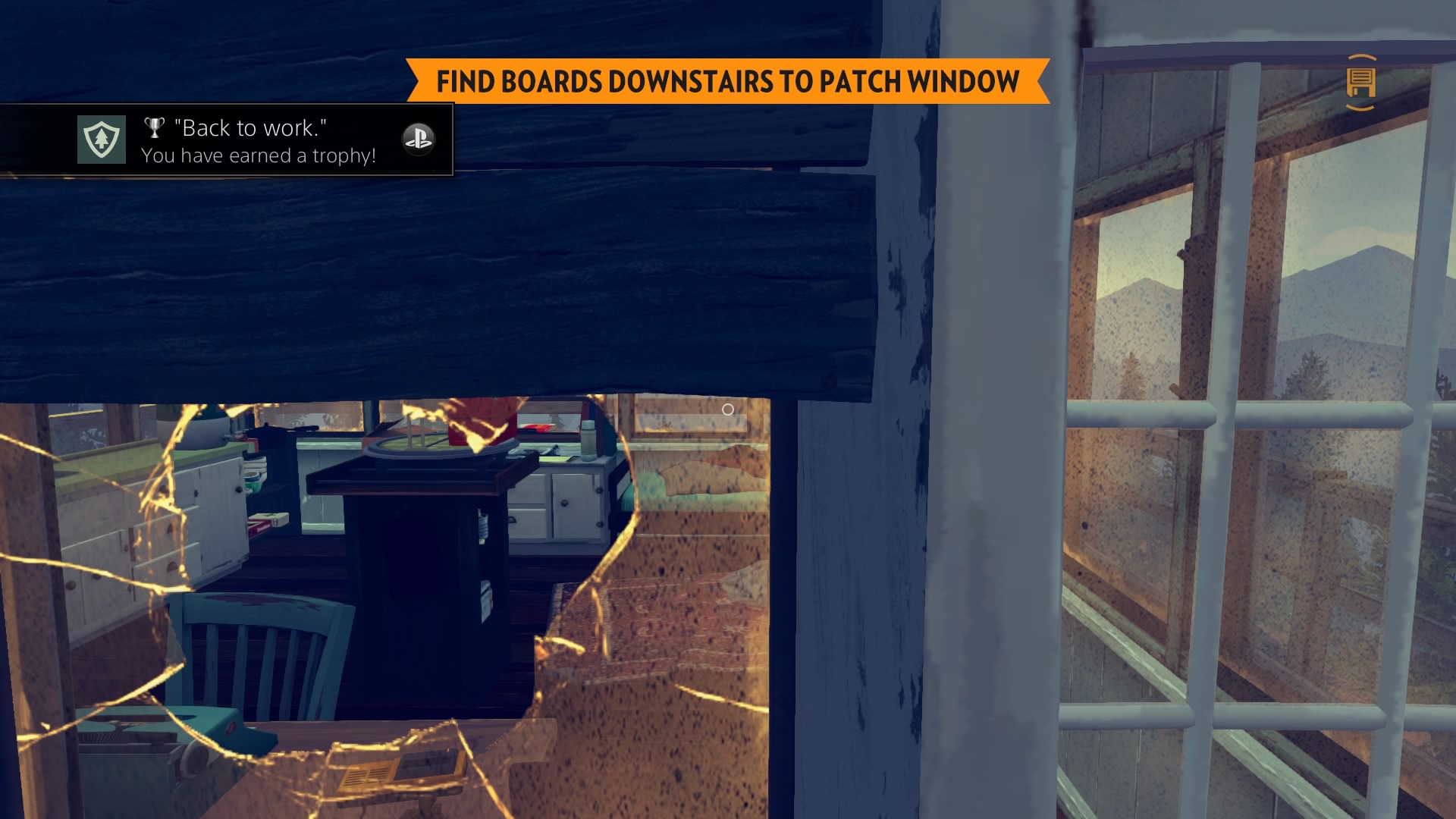

The cheeriness of the national park, once you arrive, stands in stark contrast to the opening moments, although the title of the game (as well as a "fire danger" sign pointing to "extreme") foreshadows the coming events as less than idyllic.

Where's Smokey Bear when you need him?

But let's get back to an earlier point and talk more about that other lookout, Delilah.

For most of the game, she is the only other person with whom you interact. There are other characters, a few of whom you see or interact with at a distance, and a few others still that only exist as part of narrative objects that patch together a rough history of other lookouts from summers past. Delilah, though, is a constant throughout the game; in fact, one of the main "gameplay" elements, if you can call it that, is using your walkie-talkie to communicate with her as you wander about park.

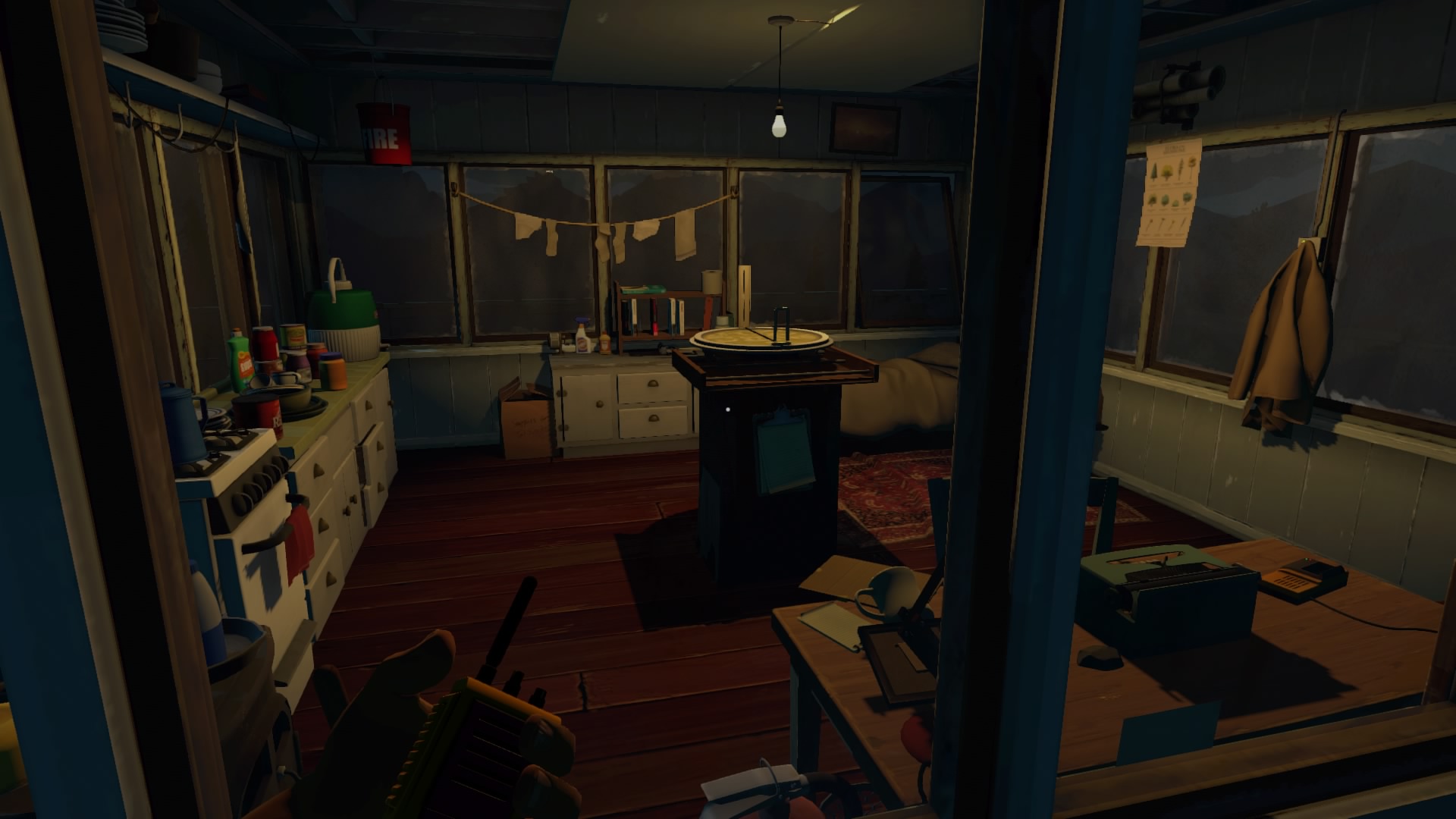

Your accommodations for the summer; don't worry, it'll look better under the light of day.

Like many games over the past decade since Mass Effect popularized the technique, interactive dialogue options fuel much of the narrative here. You can shape the details of Hank and Delilah's relationship through various answers, including silence. The pre-cell phone era of the story lets the walkie-talkie be a much more personal communication device because you can only talk the one person close enough to be in range; yet you're still afforded a narrative device that allows for a constant companion.

It's more effective than usual here simply because it's given such focus. Unlike many games that require you to walk around and talk to non-player characters (NPCs) in the environment, Delilah and Hank chatter throughout the game as he goes about his duties in the park. It's both non-intrusive and a focal point of the adventure that serves to add emotional weight to an otherwise silent place.

While the walkie-talkie is at least some technologically advanced (for the time), the other big interactive device is decidedly old-school: a paper map (and compass).

No GPS-style mini-maps here.

The map is perhaps the most jarring element when you start to really play Firewatch. Countless games over the past few generations have trained players to rely on tiny maps tucked away in the corners of your screen that show your location and orientation in real-time as you explore 3D environments. It's one of the most significant advancements in 3D gaming that came shortly after Super Mario 64 introduced us to the genre. Beyond that, modern smartphones have brought this sort of guided navigation to the real world; who hasn't brought up walking directions in a major city at this point?

In Firewatch, though, that comfort is stripped away in favor of a map that must be studied and considered. It's at this point that we hit one of the divisive qualities of the game: because the map requires the player to stop walking, actively hold it up, and get oriented using the compass, it naturally slows down the flow.

Not everyone will like this; I loved it.

For me, the map worked as a device to transport me to fantasies of pirates exploring a forgotten island in search of buried treasure, even though I was just a normal guy in the eighties. Instead of following an obvious trail or set of directions, it felt like I needed to think about traversal in much the same way as I might if I were really in this circumstance. I've talked before about the term "walking simulator," but Firewatch brings that idea to a whole new level: the "map simulator."

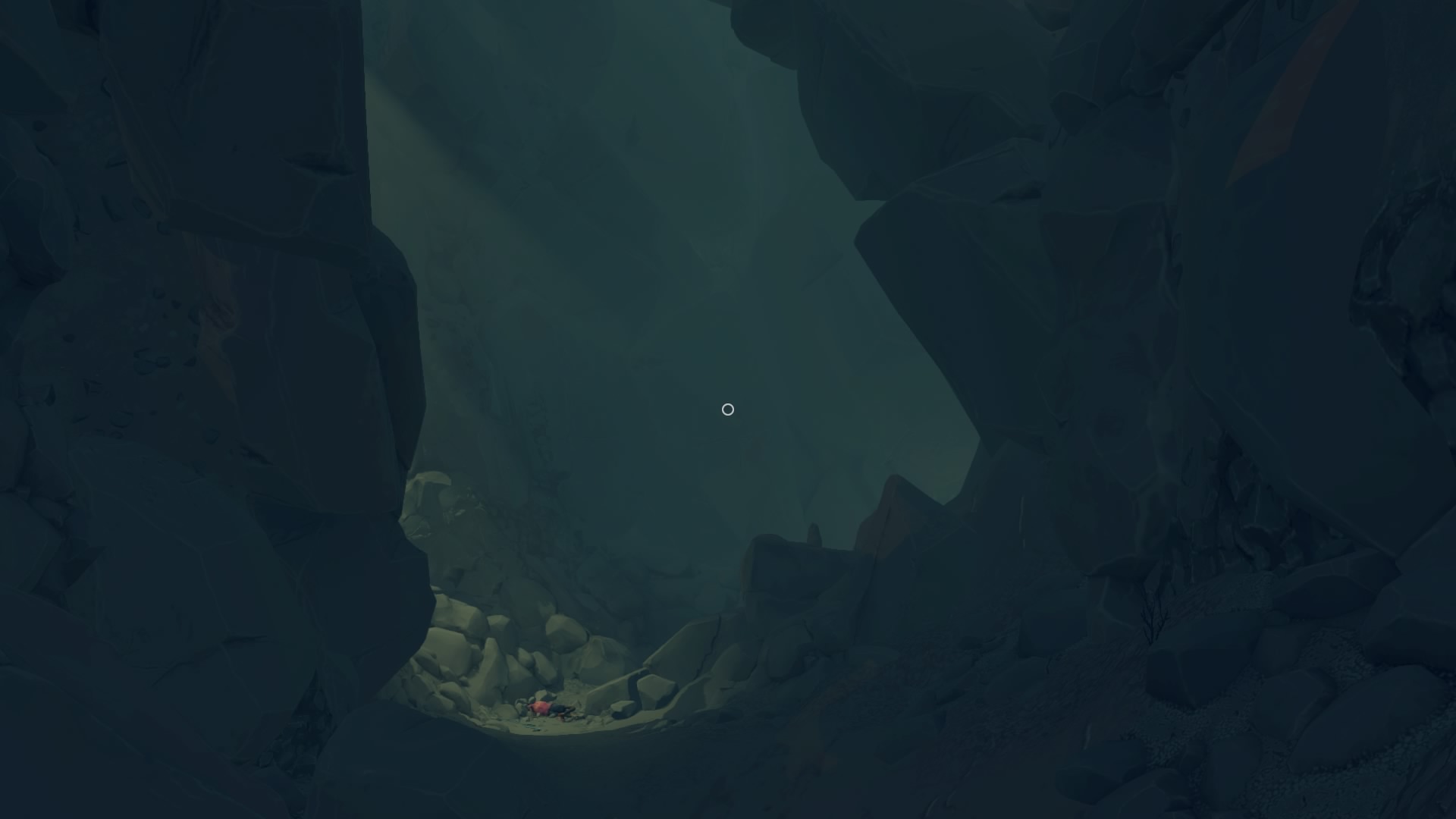

Who lived here? Too bad you don't find out.

As you scour the woods, you'll find the occasionally opportunity to stray from the intended path. For all the tantalizing ideas of what you might find out in these woods, there are some letdowns. Outside of the main story, the game does not particularly reward additional exploration.

Take, for instance, the slightly-off-the-beaten-path burned out cabin/watchtower you find (above). When I saw it from afar, my mind immediately jumped to memories of Jacob's cabin on LOST. What would I find inside? What mysteries did this cabin's existence imply?

Ultimately, the cabin was just a cabin. Perhaps the developers didn't want to overcomplicate things, but it seemed like a missed opportunity to not have some extra side narrative clues tucked away to make it worth my time to spend more time in this otherwise carefully crafted world.

Say cheese!

I compared my time with Firewatch to a summer camp—a vacation, if you will. One final element of interaction, then, that bears mentioning is the disposable camera you find near the beginning of the game. You're given a single roll of film to take about 24 pictures wherever and whenever you want throughout the rest of the game.

This serves no other purpose than: a.) being a fun diversion, b.) celebrating the game's beautiful environments, and c.) giving you a customized credits roll at the end of the game featuring your photos. By the time I had found the camera, I had already been snapping tons of my own photos via the PS4's handy Share button, but it was pretty cool to see the developers acknowledge the fun inherent in finding a great angle for that perfect virtual picture.

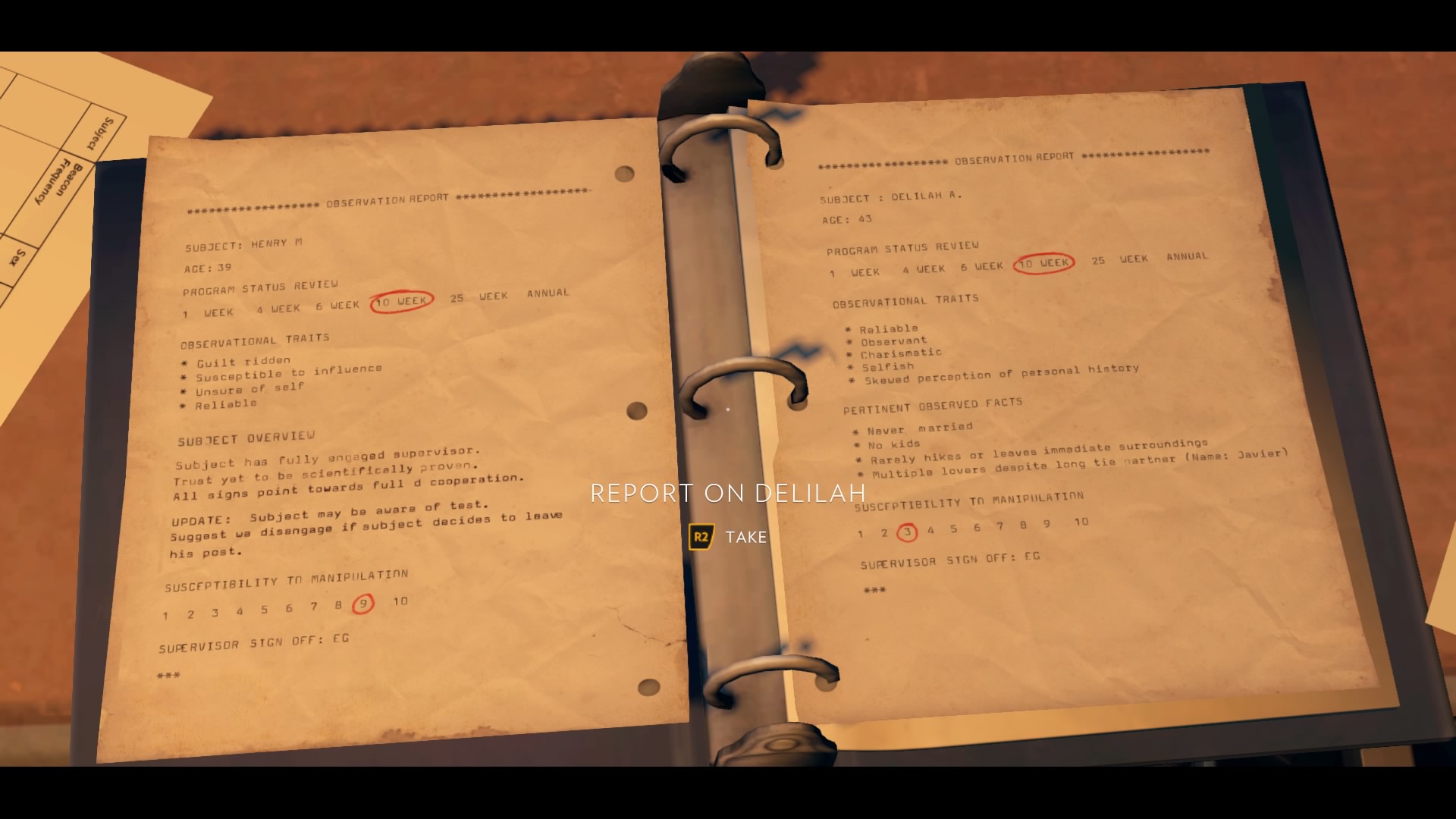

The plot thickens...considerably.

At this point, we have to talk a bit more specifically about the story.

For much of the game, it seems like an increasingly weird trip down conspiracy theory lane: there's a stranger in the woods; some drunk, teenage girls go missing; someone might be eavesdropping on your conversations; there could be strange, government experiments. Can Hank trust Delilah? Can Hank even trust his own memory? What happened to some of the past lookouts? Will Hank ever meet Delilah?

It's a solid setup with a love-it-or-hate-it resolution that will likely color your opinion of the entire game.

Like any good conspiracy nut, Hank collects notes and puts them on a wall.

I was conflicted after I finished Firewatch.

It answered nearly every question it posed by the end, yet I walked away somewhat unsatisfied. Like Fox Mulder, I wanted to believe in more than the game's ultimately-grounded narrative was willing to offer. Gone Home offered a similarly intriguing setup with a non-supernatural resolution, yet it felt somehow more satisfying than the ending here.

Endings are never easy, and I don't think the finale of Firewatch is a miss; it's just not the home run I wanted.

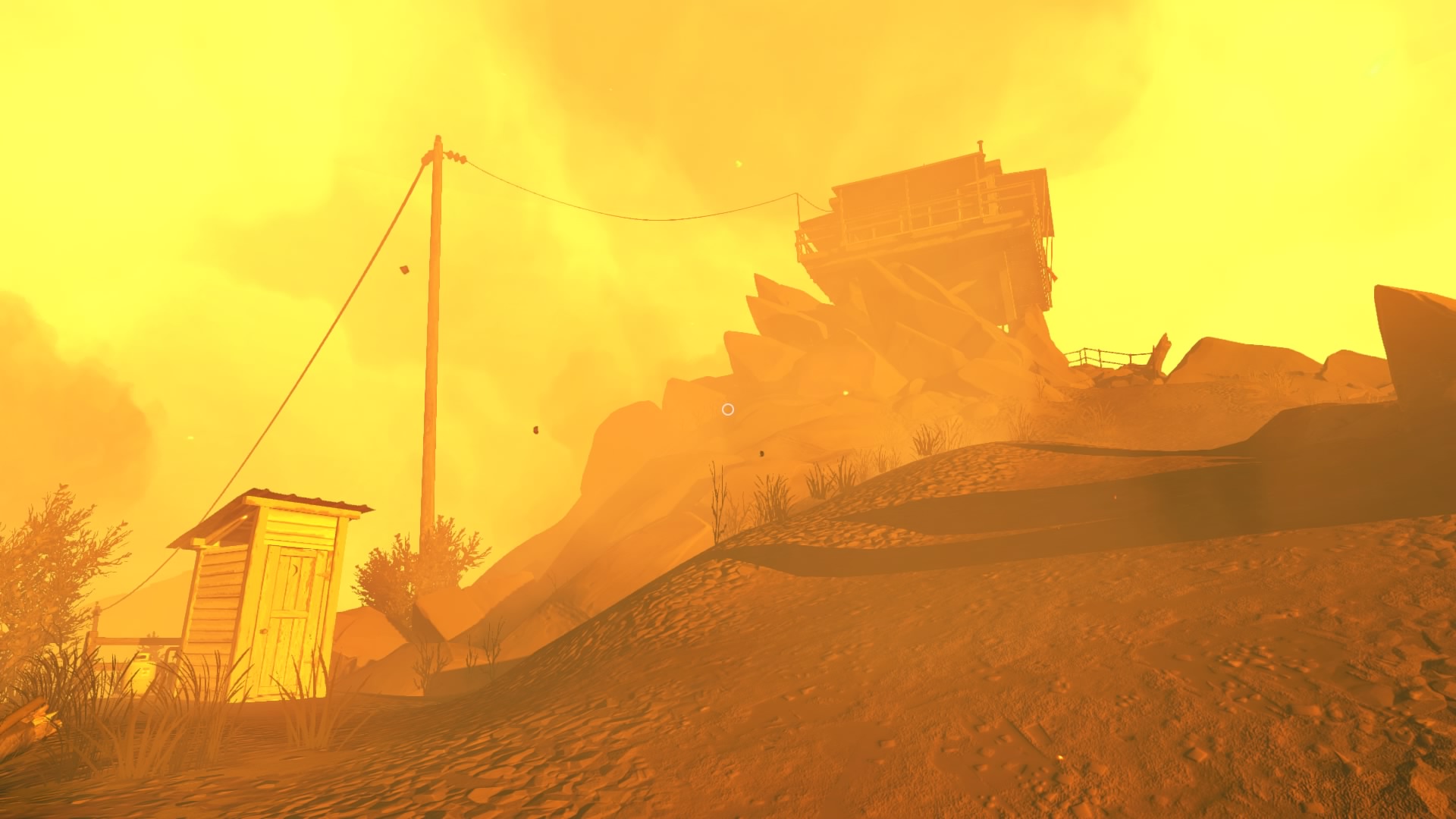

There is an actual summer camp in the game, although it's fallen entirely into disrepair.

Ultimately, though, perhaps the back-to-reality ending is the perfect send-off to this virtual summer camp. As with any vacation, when you head home, you probably haven't discovered the mysteries of the universe or solved all your problems; but you probably have experienced something that changed you. Hank doesn't end his summer as fire tower lookout a wholly different man, but I do think the journey has impacted him on a deeper, subtler level.

As the player, I think the effect is similar: when you set down the controller at the end, you're left to reflect on your time spent in this world, playing as Hank, talking to Delilah, and exploring this wilderness. All the things you thought you cared about—the mysterious man, the missing girls, the suspicious experiments—fade away in the realization that the journey is truly the destination.

MORE PHOTOS FROM FIREWATCH